Remember going on a treasure hunt as a kid? Following clues, peeking into and under things, playing detective. Fun, right?

Welcome to the world of geocaching!

Geocaching started in May 2000 when the U.S. government made GPS (global positioning system) more accessible for civilians, according to gps.gov.

One GPS enthusiast hid a target in a forest outside of Portland, Ore., posting the longitude and latitude coordinates on an internet GPS users’ group. The idea was simple: Find the container using the GPS, take something (it was filled with inexpensive items), and leave something.

By September of that year, another cacher had created a GPS hobby site with a listing of 75 known caches worldwide.

Today, there are more than three million geocaches, in 191 countries and on all seven continents, according to geocaching.com.

This high-tech treasure hunt started with techies, but today, it’s an all-ages activity. Cachers, as they’re called, use a handheld GPS or even their phone (with an app) to find hidden (but not buried) containers, hanging from a tree in a forest, under a mailbox in the city — pretty much anywhere.

Geocaching offers the thrill of the hunt, but it also invites you to learn about the earth, explore places you might not have discovered otherwise, and keep mentally and physically active.

“We like to travel with our trailer,” says Wendy Pearson (District 15 Halton), a cacher since 2018, who tagged along with her husband one day. “We find geocaching will take us to a beautiful spot, a great lookout, or a historical site, or just down roads or to towns we didn’t know about.”

Geocaching can be as easy or as difficult as you like. Levels of difficulty and terrain, known as the D/T rating, are based on a five-star scale.

Levels of difficulty run from Level 1, easy to find and typically found in a few minutes, to Level 5, requiring specialized knowledge, skills or tools.

“There are some 5s we’ve just walked away from,” says Dave Stabler (District 36 Peterborough), who has been caching since 2006; he discovered the activity in a magazine article. “When that happens, you go back to the website and log a DNF [did not find].”

Terrain is similar: Level 1 is typically less than a one-kilometre (flat) hike and wheelchair accessible; Level 5 involves using equipment. “People carry ladders, kayaks, scuba equipment,” says Stabler. Some even climb cliffs to find caches. “We’ve never done that, but we have used the odd ladder.”

Geocache containers can be any size. The largest Stabler has found is a 45-gallon drum, though he says there are some in the U.S. that are shipping containers. Some (not all) caches contain inexpensive, tradable items, such as pencils or little action figures. “Kids like geocaching because of items,” he says. “You put something in and take something out of equal value.”

Trackables, like a coin or a dog tag, are tracked on the geocaching website. If a cacher finds a trackable, they take it with them, register on the website where they picked it up, and then where they dropped it off. “You can watch as it travels around the world,” says Stabler. “We’ve had trackables end up in Switzerland, Arizona and France.”

Gadget caches offer an added challenge. “They’re usually easy to find, but you have to get into them,” says Stabler. It could be something like a combination or a push/pull device. Stabler remembers one in Cobourg, Ont., where you had to tune in to a radio station in your car to hear the combination to open the box.

EarthCaches are another kind of geocaching. There’s no container to find; instead, you do research at the location. Find the EarthCache, answer the questions from the cache web page, and send them to the EarthCache owner. “It’s almost like a school project,” says Stabler. “You get credit for doing a cache, but you’ve learned something.”

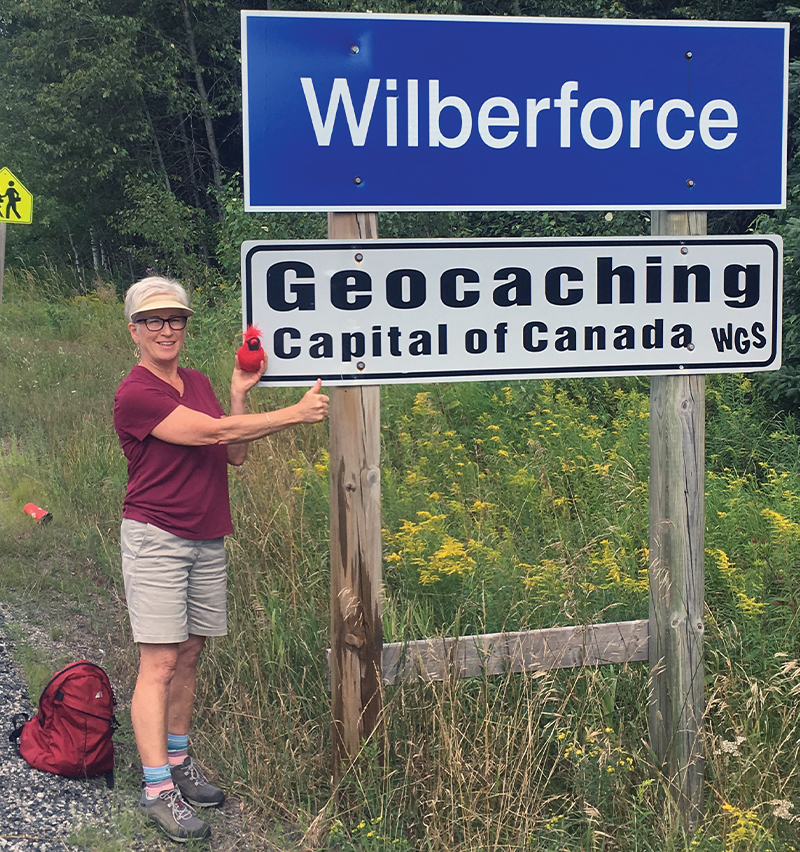

The really cool thing about geocaching? It’s global. Both Stabler and Pearson have cached in almost all of the provinces. And Pearson has cached in Florida and in Slovenia.

Bruce Clark (District 23 North York) was researching geocaching for the second edition of Making Connections: Canada’s Geography, which came out in 2006, and found a cache in Suwarrow, one of the Cook Islands. “At the time, I was recently retired and my wife and I were in the process of starting a sailing trip around the world,” he says.

If you’re thinking about hiding a cache, geocaching.com suggests finding at least 20 caches before you become a cache owner/hider, so you know how to create a good experience for cachers. (You can find hiding guidelines at geocaching.com/play/guidelines.)

Stabler has hidden 350 or 370 — “somewhere around there.” As for Pearson? She’s preparing to hide her first cache, a “letterbox,” which has a stamp in it, similar to the kind scrapbookers use. (Cachers carry a little book and stamp it with the geocache’s stamp.)

“I’ll hide it close to home, so I can maintain it properly.”

Getting started

Sign up for a free account on geocaching.com. Use a “fake name” for security purposes, says Dave Stabler.

“Get the app on your phone [first] to see if it’s even something you like,” says Wendy Pearson, “because it’s not for everybody.”

Download coordinates to your phone/GPS. Look for an easy level for difficulty and terrain first — a 1 or 2, says Stabler.

Head out to find the cache. When you find it, open it up, and sign and date the logbook.

“If you’re going into the woods, be smart,” says Stabler. “Take water, dress appropriately, look for poison ivy, take a first aid kit.” And mark your car on your GPS or your phone in case you get lost.

If you opt to buy a GPS, get advice on a good handheld one. “A friend of ours bought one and it’s tiny and very hard to manipulate,” says Pearson. “She has trouble reading the screen.”