New research is challenging the idea that heart disease is a “man’s disease.” For an update, Renaissance spoke to two Canadian experts in the field: Karin Humphries, PhD, an associate professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (UBC) who holds the UBC Heart and Stroke Foundation Professorship in Women’s Cardiovascular Health, and Paula Harvey, MD, PhD, who’s the head of the Department of Medicine and holds the F.M. Hill Chair in Women’s Academic Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Heart disease in women can look quite different than heart disease in men. Women’s bodies are built differently, their hearts and coronary vessels are generally smaller, and they present with unique symptoms.

First of all, risk factors for heart disease affect women differently than men. For example, type 2 diabetes is twice as likely to lead to heart disease in women. Smoking is also especially hard on a woman’s heart.

Some heart disease risk factors, for example hypertension (high blood pressure), are often not picked up on or treated as promptly in women as they are in men.

Some risk factors affect women almost exclusively. In addition to breast cancer, these can include autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis, which might cause inflammation of the blood vessels or plaque buildup.

Women who had high blood pressure during pregnancy or gestational diabetes are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease as they get older. To prevent later-life hypertension, it’s important to regularly monitor blood pressure. “Every time you go for an annual exam, get your blood pressure checked and make sure it’s not going up. If it is, it needs to be treated,” says Humphries.

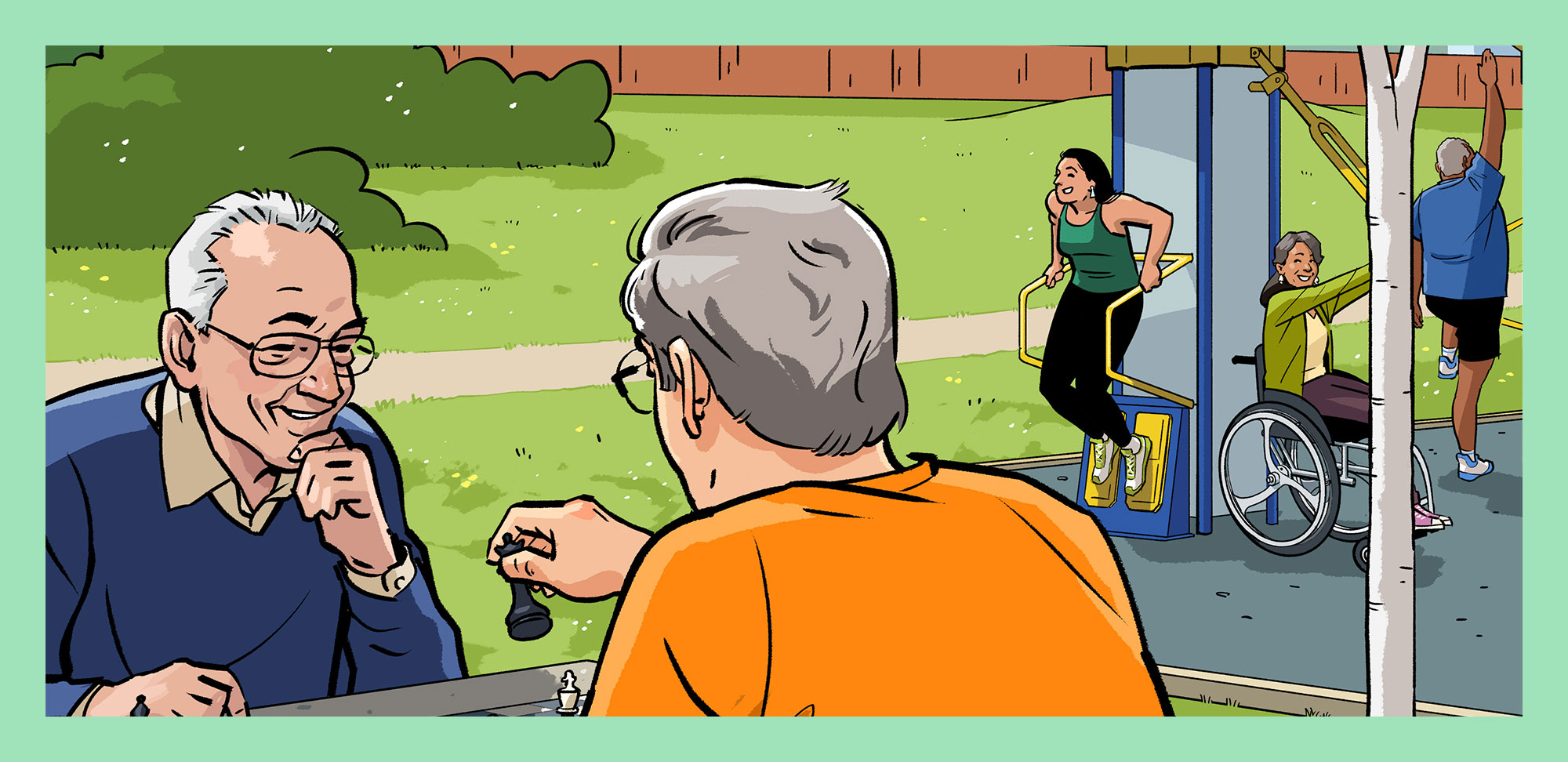

Eating well, maintaining a healthy weight and getting regular exercise are also key to heart health. But instead of a single workout or physical activity a day, Humphries advises, “try to increase physical activity throughout the day because the benefits are cumulative.”

Women who suffer heart attacks often don’t present the same kind of symptoms as men do. You know: the classic sharp chest pain described by men. Instead, women might feel a heavy pressure in their back, extreme fatigue, jaw pain, nausea or sweating — symptoms that may be misdiagnosed or dismissed by health care personnel, says Humphries. These unique symptoms may be because the disease affects the heart’s smaller blood vessels rather than major arteries. Women’s smaller coronary arteries make procedures such as bypass surgery more difficult to perform, and this increases their chances of a poorer outcome.

Research has historically focused on men, but that’s changing. A recent study in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology uncovered a concerning increase in heart attacks among Ontario women under 55 years. The findings suggest women do as well as men a year after a heart attack, but only after adjusting for risk factors. “They are doing worse than men, and it’s because they’re obese, and it’s because they have hypertension and diabetes,” says Humphries.

But women are also less likely than men to be prescribed blood pressure or cholesterol-lowering medications after a heart attack. And they’re less likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation, or if they are referred, they drop out because they’re uncomfortable exercising with men, says Humphries. Or they may be caring for children or elderly parents while still holding down a job and can’t get to rehab sessions during the week. And transportation is a concern for women living alone and struggling economically, says Harvey.

The good news: Experts are working to customize cardiac rehab, offering classes for women only, as well as virtual and weekend sessions.

The debate continues about whether menopause increases the risk of heart disease because of the loss of the protective effects of estrogen.

Past research has found that hormone replacement therapy didn’t protect women against heart disease, but it studied only women who had been menopausal for some time, says Humphries. “Had we given estrogen closer to when they went through menopause, maybe we would have seen some benefit.”