By Barbara Rogelstad (District 40 Brant) as told to Martin Zibauer

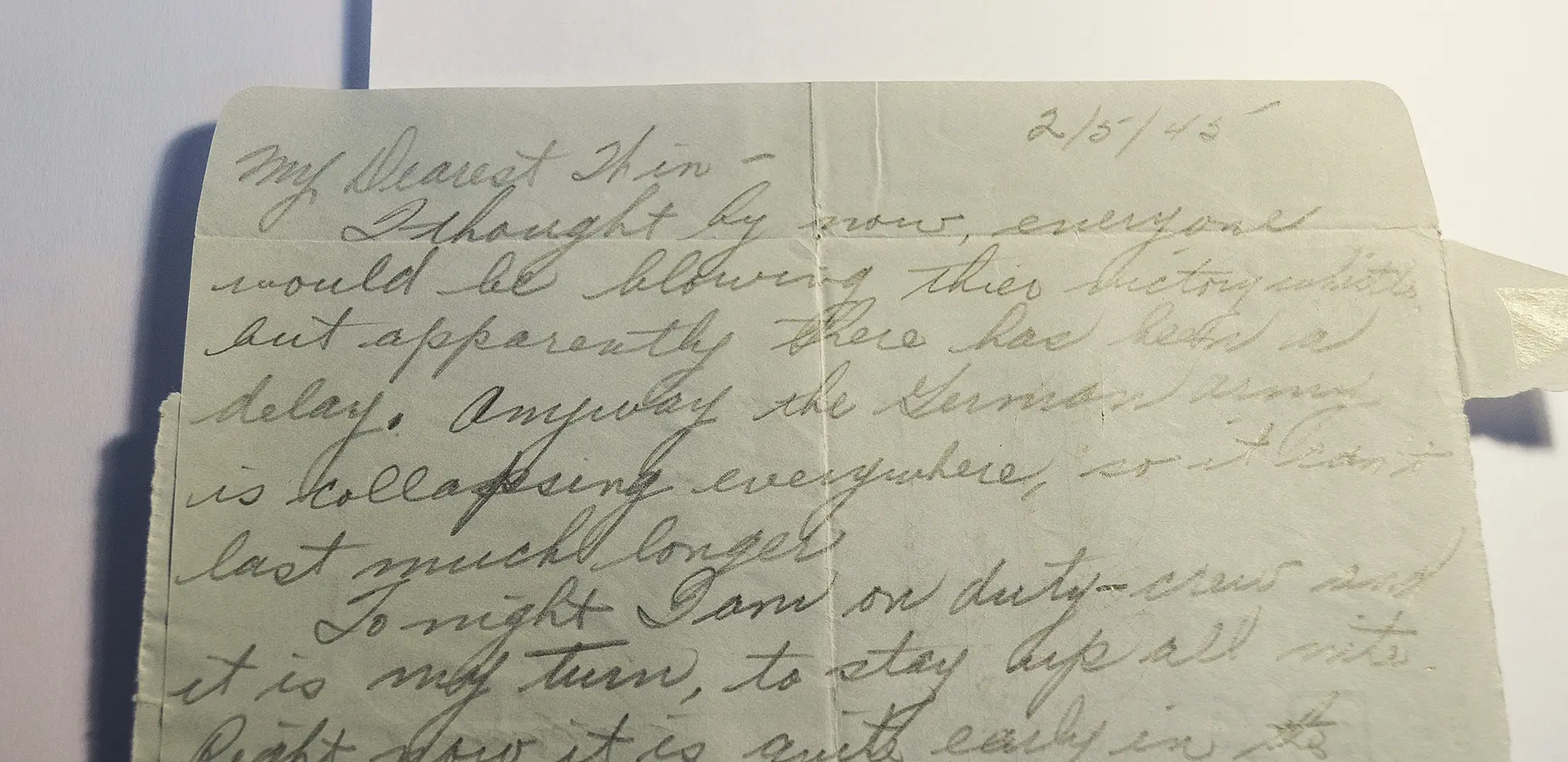

“I have about 400 letters that my father, Patrick Parrott, wrote to my mom during the war. He was a pilot officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force, in the 437 Transport Squadron.

“He wrote home several times a week. My mother, Winnifred, kept the letters, and after she died, my father held on to them. One of my bucket-list retirement projects is to pass them to my kids and grandkids; not in a shoebox they’ll have to sort through, but in an electronic document they can access and share.

“Mothers often carry the details of family history, but because my mother died when she was only 48, much of my parents’ background is foggy. I only have one side of the story — the boxes have only my dad’s letters.

“I once asked him, ‘Where’s your shoebox, with Mom’s letters to you?’ The RCAF airmen, he said, were allowed only a small container for their uniforms, badges, medals and anything else they wanted to bring home after the war. He just couldn’t fit all the letters he’d received. He had to leave Mom’s letters in England.

“I’ve had the boxes for years, but I spent a long time just looking at them, wondering what to do. I started by putting the letters in chronological order and into protective sheets, and then into binders. But I couldn’t just give my kids two huge, cumbersome binders and say, ‘Pass them around.’

“A few years ago, I began transcribing the letters into an electronic book. I copied them exactly as my dad wrote them, with the spelling and grammar mistakes. If he spelled out an abbreviation or underlined something, so did I.

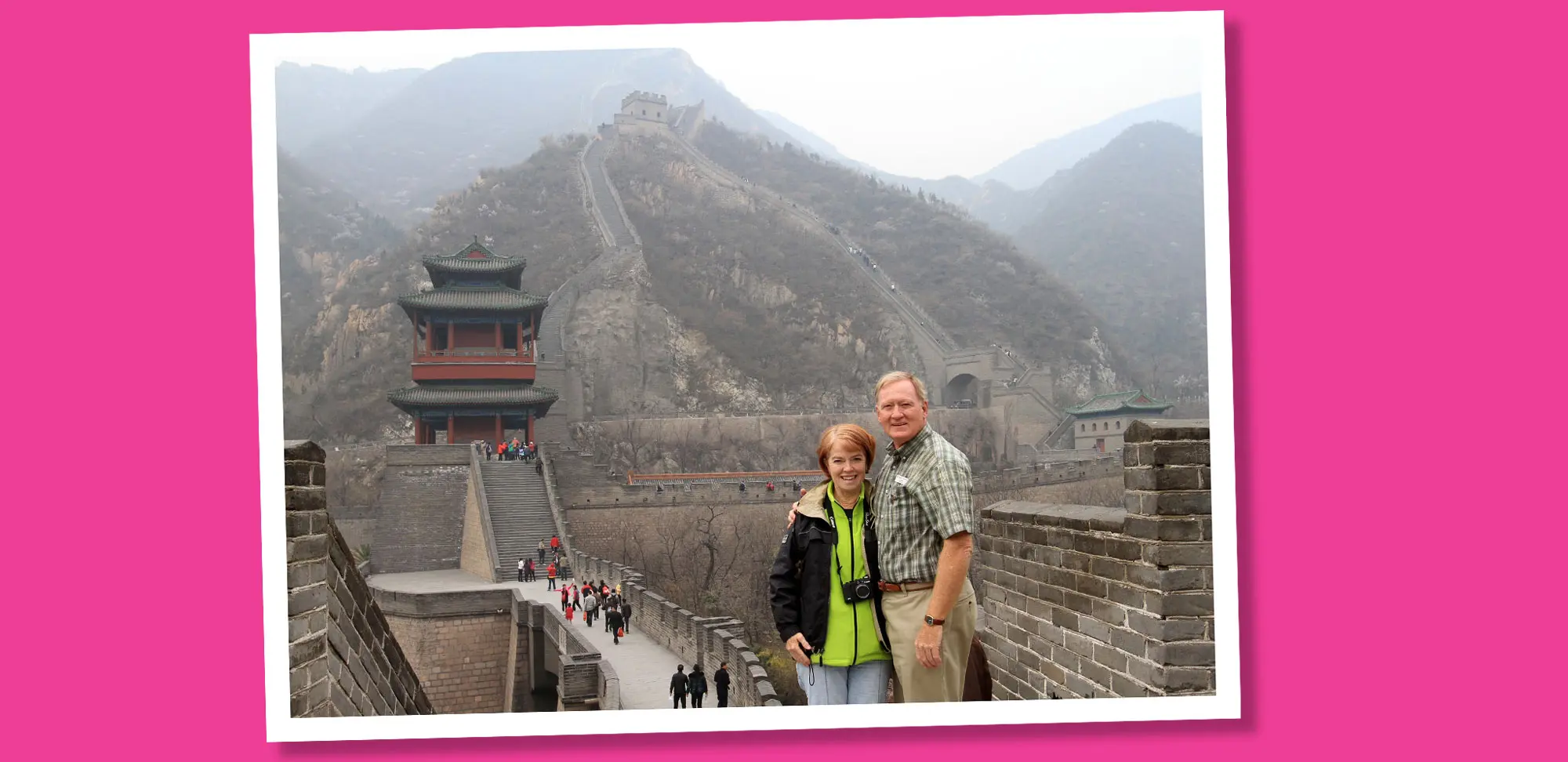

“Now, I’m scanning my old photos and adding bookmarks for every name he mentions. Clicking on a name links to other pages it appears on. I’m part of a Lambton County genealogy group, and some members have parents who my dad mentions. I can easily find stories and information and pass them on. Transcribing Dad’s letters from 75 years ago has connected me today to people who share a link with my family history.

“The first letters start when my dad enlisted and began training, first in Toronto and then Montreal. My mother then was working in the war department at Mueller’s in Sarnia. Mueller’s transitioned from manufacturing plumbing supplies to munitions. My dad worried about her.

“At one point, my parents made plans to both take trains to Toronto to meet at the King Edward Hotel — Dad was afraid he’d be sent overseas before they could get married. My mom told her parents she was meeting up with a girlfriend. It’s odd to read about your parents doing what was considered improper then, but they were young and the letters make it clear they were crazy in love.

“He came home for a couple of weeks when they got married, and then went back to finish his flight studies in Montreal, at McGill. The letters start to show a real sense of commitment and maturity. He’d apologize for not writing much; he was studying hard for exams he needed to pass to become a pilot. He seemed to really dig deep at that time and commit to serving his country.

“Many of the pilots, including my father, aspired to become bomber pilots. Bomber pilots were very skilled, flying planes at night, in all kinds of weather and in the chaos of fighting. But he stayed in transport services throughout the war, picking up the wounded and prisoners of war, sending gliders in, even flying paratroopers over. Dropping paratroopers required flying very low and was more dangerous than other missions.

“The pilots would check to see if they recognized the wounded soldiers. A number of times, my mom asked him to look out for someone specific. Matt Ness was one name; he was missing and his family didn’t know where he was. Perhaps Matt was badly wounded and didn’t know who he was and my dad might recognize him. When Holland and France were liberated, my dad spent time in hospitals there visiting injured soldiers, and he actually did reconnect with some old friends that way.

“As the war in Ukraine is unfolding, I’m seeing parallels to my dad’s letters. Here we are again, sending Canadians over. Although they’re not right in the war in Ukraine, they are prepared for it. That’s what my dad was doing at first: flights at night, in the fog, in the winter — just to make sure they could get over to the continent and back no matter what.

“After he was stationed in England, the letters became more serious but much less detailed. In 1944 and ’45, he couldn’t reveal where he was. If anything he wrote gave away too much, military censors would cut out details — they’d actually cut away the paper with scissors and stamp the letter ‘Censored.’

“The letters express his hope that one day he and Mom could move into their own home — she lived with her parents while he was away. She loved dancing, she played piano by ear, she hung out with her girlfriends and would go with them to dances on weekends — these are details I learned from the letters. Along with some odd tidbits: She really enjoyed painting walls.

“He often asked my mother to send ink, pens and paper — all hard for him to get in wartime. And he wanted to know if Mom was hearing the same songs on the radio, which ones were popular, and my mom’s opinion of different lyrics. He wrote about Vera Lynn’s ‘We’ll Meet Again’ — and other songs that, it seemed, brought up strong feelings for my dad and made him think of his wife and home. I believe he used music to trigger the love they felt and to stay connected.

“My dad would reminisce about Saturday nights spent dancing in Kenwick Park on the shore of Lake Huron, close to Sarnia. Through my own teenage years, there were dances with live bands there. We’d be dancing on essentially a cement slab with a stage. But it was outside, by the lake, and candlelit — it was beautiful. And the same dances happened there when my parents were dating. We all share that experience.

“Soon after the war ended, his buddies in the navy and the army starting going home. But for months, the pilots were still dealing with the aftermath. My mother sent newspaper clippings of the VE Day celebrations in Sarnia. He wrote, ‘I wish I could have been there to dance in the streets, but we still have work to do over here.’

“The airmen would wait for their ‘number to come up,’ when they could take the boat home — at one point he wrote he was number 95, then 93 and so on. He did consider staying on in the RCAF. He would have moved up in rank and pay, but at this point he’d been away four years. Four years and 400 letters.

“Recording his letters, for me, is a labour of love and a gift for my kids. I can make it easier for them to learn about their grandparents. For my brother, too, it will be such a gift to read through the letters and all the details of Mom and Dad.”