As a child, Dianne Waun (District 9 Huron-Perth) took piano lessons. “I hated every second of it!” she recalls. Piano didn’t last. When her kids were young, Waun tried playing trumpet in a community band. “No luck there,” she says.

She thought her musical aspirations were over. Not quite. Waun, who lives in Exeter, Ont., was 18 years into retirement when she heard the Bayfield Ukulele Society at a community event. “They were having so much fun. I wanted to be one of them,” she says.

In 2018, Waun was 72; she asked her children to give her a ukulele that Christmas. They did, and she started taking classes weeks later. Seeing other players made her confident instead of intimidated. “I thought if they can do it, I can too,” she says.

Many adult beginners have the same can-do attitude. They realize that it’s never too late to pick up an instrument, learn a language, start a hobby, return to school, or pursue a long-held dream.

Young people may be wired to learn, but it isn’t their exclusive domain.

In the recent book Beginners: The Jay and Transformative Power of Lifelong Learning, author Tom Vanderbilt describes the “awkward, self-conscious, exhilarating dawning of the novice.” He writes that beginning is “about small acts of reinvention, at any age, that can make life seem magical — it’s about learning new things, one of which might be you.”

That was true for Waun. Within a month of starting her lessons, she learned that the Bayfield Ukulele Society wanted more players to fill out a stage. Waun only knew two chords but asked if she could join. She did, faking it but having a blast.

Since then, Waun has continued learning. During the pandemic, she joined virtual jams with ukulele groups all over North America. N ow she plays with the ukulele society weekly and has picked up the banjolele (ukulele neck and banjo-type body) and the bass ukulele. Waun can manage about a dozen chords now, but proficiency isn’t the point. When she plays, she says, “I feel invigorated, inspired and uplifted.”

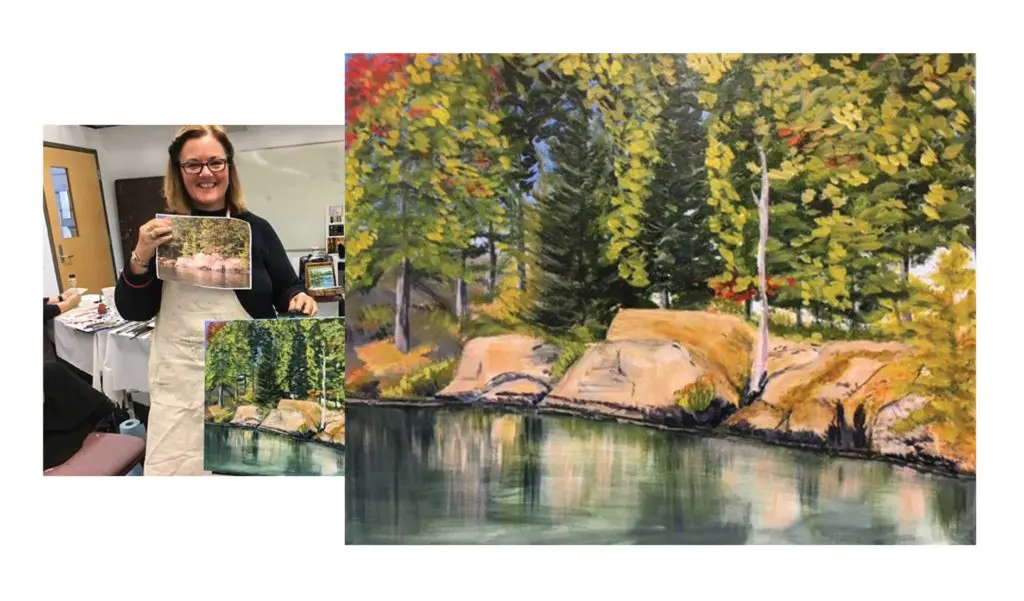

Painting affects Karen Miller (District 37 Oxford) in a similar way. “It feels calming, almost meditative,” she says.

When she retired in 2015, Miller considered new ways to keep busy. A few acquaintances asked if she wanted to come out for a night of painting. “I didn’t set out to be a pain ter. I t was just a way to keep connections and be social,” she says. But at age 60, Miller caught the art bug. She wasn’t worried about what the final product looked like. “I enjoyed the creativity and the completion of it. And it gave me a purpose to challenge myself.”

Miller began picking up painting tips online and from other artists in the community. Now she paints about three times a week in her rec room. She works in watercolours, oils and acrylics, and mostly does landscapes (@kmartpainting on Instagram).

As an adult beginner, Miller says her learning curve was a bit longer, but she also had the hours to devote. “Retirement gave me the time to dive into it,” she says.

She has never let a fear of not being great stop her from trying. “Not being perfect in my painting never bothers me,” Miller says. ”I’m doing this for me. I can always strive, but I’m not afraid to make mistakes and experiment.”

I t helps to remember that nobody is judging you.

“That’s the biggest thing. There’s no test,” says Deborah Bonk Greenwood, executive director of the LIFE Institute, a leader in lifelong learning for adults 50-plus through continuing education at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University) in Toronto.

Bonk Greenwood says older learners often feel that young people pick up things more easily and quickly, so why bother learning past a certain stage in life. “Society has programmed us that way,” she says, and many older adults internalize that ageist attitude. “But you never lose your curiosity.”

Eighty-four-year-old Aubrey Millard (District 3 Algoma) has satisfied his curiosity the world over since his retirement in 1998.

He left teaching that January, at 59, and in July 1998 he and his wife, Judy, made a huge life change. They sold their Toronto home, took their 32-foot sailboat around the Great Lakes, and just kept going. The couple ended up living on the boat for the next 20 years.

Many people fantasize about chucking their old life to hit the road (or seas), but few have the nerve to do it.

“The night we sold our house, my wife said, ‘Do you have the smell of burning bridges?’ We wanted to see the world,” says Millard.

And that they did, sailing more than 65,000 nautical miles: down to the Gulf of Mexico, into the Caribbean and Bahamas, across the Atlantic via Bermuda and the Azores to England, up the Seine to Paris, down the Rhone to the Mediterranean… Spain, Tunisia, Malta, Croatia, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, the Canary Islands and Cape Verde Islands, Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Colombia, Venezuela, the west coast of British Columbia and Alaska.

Millard had been a Royal Canadian Navy reserve officer throughout his teaching career, and the Millards had their boat for a few years before embarking on the two-decade odyssey, so they had the sailing competencies. Still, sailing the world full-time requires another level of skill and confidence. “You have to be very independent. There are no plumbers or mechanics when you’re in the middle of the ocean,” says Millard.

The couple returned to Canada in 2017 and now live in Elliot Lake. The pandemic slowed their travel, but the winds and currents may take them on more journeys. ”I’m not sure what the next stage is, but we’re not finished yet,” Millard says.

A 2017 study in Human Development noted that across life we go from broad learning (many skills as a baby or child) to specialized learning (expertise in an area, like work skills). The study argued that older adults can find success by returning to the mindset of childhood learning: Be open-minded, leave your comfort zone, let yourself fail, find teachers and mentors to guide you, and understand that effort reaps rewards.

You’ll likely experience physical and mental health benefits, too. Some studies show that your mood can be elevated when you learn and do something new — not surprising, given the sense of fun and achievement you can experience.

A study in the Journals of Gerontology in 2019 also pointed to improved brain health. Research subjects aged 58 to 86 took three two-hour classes a week, two on one day and one on the next, for three months (anything from Spanish to photography). Participants completed cognitive assessments before, during and after their studies. After just 90 days, participants improved their memory and cognitive control (switching between tasks) to a level similar to adults 30 years younger.

The researchers concluded, too, that learning several new things at once is part of what’s beneficial. So if you’re anxious about tackling one new thing, try two, three or more.

Andy Hanson (District 19 Hastings and Prince Edward) has taken that to heart. Since retiring in 2010, He has tried one new pursuit after another.

It started with earning a PhD in history from Trent University in 2013, at age 64. The degree was a means to an end: He wanted to write a book about the teachers’ union movement but lacked the research and analytical skills. After graduating, Hanson shopped his dissertation around. Several publishers rejected the idea, but Between the Lines Publishing thought it had potential, and Hanson’s book, Class Action: How Ontario’s Elementary Teachers Became a Political Force, was published in 2021.

Getting his PhD gave Hanson the confidence to go on a run of new pastimes. He took ballroom dancing and French lessons and became a movie extra. His claim to fame: a glimpse of him in the background of a Jessica Chastain-Idris Elba scene in Molly’s Game, filmed partly in Toronto.

Now, Hanson is thinking of getting a surfboard and learning to kayak. He already canoes, and that has also taught him something about taking the plunge. “When you’re running a river and entering a rapid, there’s a point where you can’t turn around. You’re engaged, and there’s no fear. You don’t have space for it,” he says.

Learning to embrace risks is part of a never-too-late attitude. Hanson says the time it takes to complete a PhD, or do anything new, will pass regardless. The question is how you’ll feel when you look back.

“Will you feel better if you tried,” he says, “or if you didn’t?”