A few years ago, the Guardian in the U.K. ran an article on misconceptions about Canada. The paper used an illustration of a Mountie, holding a hockey stick and downing a brew, astride a polar bear wearing a Blue Jays cap, overlooking a tuque-wearing lumberjack chopping down a tree on a frozen tundra broken up only by an igloo.

The illustration was being cheeky, but the article wondered: How easy is it to define “Canadian”? “Canada,” the writer opined, “is often pictured as a uniformly cold, multicultural, socialist paradise full of beer-swilling ice hockey fans.”

The illustration was being cheeky, but the article wondered: How easy is it to define “Canadian”? “Canada,” the writer opined, “is often pictured as a uniformly cold, multicultural, socialist paradise full of beer-swilling ice hockey fans.”

The question of what it means to be Canadian has challenged us since Confederation. On May 25, 1867, George-Étienne Cartier, a soon-to-be Father of Confederation, likened the new union to a tree whose branches extend in many directions. Evocative, but not exactly inspiring — and not exactly precise.

On CBC Radio in 1972, host Peter Gzowski asked listeners to finish the phrase “As Canadian as…” to compete with the simile “As American as apple pie.” The contest winner: “As Canadian as possible under the circumstances.”

Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian academic, philosopher and media theorist, said in 1963, “Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.” But maybe our lack-of-identity-as-identity starts with our origin story. Canada was born from conferences and consensus, not revolution, as was the case for our southern neighbours and many other countries.

One could argue that this has shaped our national character ever since. The Canadian “brand” means we look for ways to get along. The Americans have as a founding ideal “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The French have “liberté, égalité, fraternité.” Our take on the tripartite motto: “peace, order and good government.”

As rallying cries go, that’s tepid. But consider that Canada was born just two years after the end of the U.S. Civil War, notes Michael Adams, author and president of the Environics group of research and consulting companies. We preferred peace over war, order over chaos, and good government as a cornerstone. “It’s where we work out our differences,” Adams told Renaissance.

So what makes us tick or stirs our national pride? In one of their 2020 Confederation of Tomorrow reports, the Environics Institute for Survey Research asked about situations that make people feel more Canadian. At least three in five people cited seeing war veterans honoured on Remembrance Day, watching athletes competing for Canada, celebrating Canada Day, travelling to other countries or hearing the national anthem. About half of respondents felt a lot or a little more Canadian when they thought about Canada’s natural resources, used their health card, or read or heard about the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada’s Constitution. Incidentally, new Canadians were more likely than those born in Canada to say they felt more Canadian in almost all the situations presented in the survey.

Previous Environics research explored what binds us together in this country. One survey found that citizenship is about much more than having a Canadian passport, obeying the law and paying taxes. What makes us good citizens, Canadians said, is:

- Treating men and women equally (95 per cent)

- Accepting those who are different (82 per cent)

- Protecting the environment (80 per cent)

- Respecting other religions (65 per cent)

- Actively participating in one’s local community (51 per cent)

We get a glimpse at Canadian values from other surveys that ask about the things and concepts that characterize us. In studies by public-opinion research firms Abacus Data, Ipsos and Nanos, these items get high marks:

- Our universal health-care system

- The right and freedom to live as we see fit

- Open-mindedness toward others

- Caring for the world around us

- Social justice

- Kindness and compassion

- Peacekeeping by the Canadian Forces

- Our steadiness and consistency

How we see ourselves is revealing, but so is how others view us — and how we think they do in return. In a 2018 Abacus survey, Canadians said they feel the rest of the world sees our country as being tolerant (93 per cent), diplomatic (93 per cent) and ethical (88 per cent). The vast majority believe we’re seen as an example to emulate (79 per cent).

Canada did indeed fare well in the 2020 Best Countries rankings from U.S. News & World Report, BAV Group and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. We came in second overall (after Switzerland). Among the nine categories that generate the rankings, Canada was second in citizenship (which looks at issues like human rights, gender equality, care for the environment and progressive culture) and first in quality of life. The commentary on the rankings noted another attribute: the way Canada encourages all citizens to honour their own cultures, and celebrates diversity as a strength.

What about Canadian stereotypes?

Are they earned? Let’s start with this one: Canadians are polite. Researchers at McMaster University put this concept to the test by analyzing discourse on Twitter. They collected 40 million tweets from Canadian and American accounts, and tracked which words were overrepresented in each group.

For Americans, some of the trademark words were hate, tired and mad (and this was all pre-Trump). In contrast, Canadians were more likely to use words like great, thanks, amazing and happy.

That may be minor evidence, but if being polite is, in fact, part of the Canadian psyche, that may date back to our roots. Nelson Wiseman, director of Canadian Studies at the University of Toronto, told Maclean’s we had a strong tradition of centralized regimes with the French, and then as a British nation. That made us more subordinate or deferential.

Moreover, Wiseman explained that while the U.S. places more value on the individual (which can make people appear more selfish), Canada has a more collective nature. We have a we’re-all-in-this-together attitude.

Now what about the cliché that we’re a welcoming nation? It seems to be true, and is growing.

For four decades, Environics has surveyed Canadian attitudes toward immigrants. The level of acceptance and support has been going up for years, and is now at its highest level. As reported by Environics in the fall of 2020, 56 per cent of Canadians say we need even more immigration, and 84 per cent say immigration has had a positive impact on Canada. The main reasons cited: It adds to our diversity and helps our economy grow.

“What does it take to be ‘one of us’”? was a question posed by the Pew Research Center in a survey of global attitudes. Pew asked people in Canada, the U.S., Australia, Japan and 10 European countries about their national identity. Only 21 per cent of Canadians surveyed agreed that being born in the country was very important to truly being one of us. That was well below the average for all 14 countries surveyed. In eight of them, more than one-third of respondents said you had to be born in the country to be one of us; in three, more than half said so.

The Canadian attitude reflects the melting pot versus mosaic argument. In other places, you fit in, said Anthony Wilson-Smith, president of Historica Canada, in an interview with Renaissance. Here, you can be yourself.

Still, being ourselves can also mean defining ourselves against others. There’s a reason why Canadians often like to brandish the Maple Leaf when we travel. It’s to make sure people know we’re not American.

A distinguishing habit for many Canadians is to compare ourselves to the U.S. Canada has one-tenth the population and nowhere near the international influence. We often seem to suffer from an inferiority complex when we compare ourselves to our bigger and brasher neighbour. That said, we can get pretty smug when we compare the state of our health care, race relations and political discourse with that of the U.S.

Actor and comedian Robin Williams, when asked to describe Canada, once said, “You are the kindest country in the world. You are like a really nice apartment over a meth lab.”

After all, consider a country where 24 per cent of the population says they have often or sometimes been victims of discrimination. Or where 84 per cent of white people surveyed say race relations in their community are generally good — but 54 per cent of Black respondents and 53 per cent of Indigenous ones report ongoing race-related discrimination.

Hold on though — that’s not the U.S. That’s Canada, according to studies from the last two years conducted by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation and Environics.

Surprised? While we pride ourselves on being the model of an inclusive society, we don’t walk the talk. Perhaps racism is one more thing we’re polite about. We certainly have work to do.

That said, Canadians are, in many other respects, caring and respectful people. Adams wrote a seminal book on the values of Canada and the U.S. called Fire and Ice. He has pointed out how Americans have more of a winner-take-all ethos, and are more consumerist, exclusionary and violent. Canadians are less xenophobic, less materialistic, more inclusive and more acceptant of societal change.

For more than five decades now, Adams says Canada has been on a “progressive trajectory.” We’re more pluralistic, he says.

Generally, our model also isn’t a society of rugged capitalism, with winners and losers, but a place where we get together and arrive at solutions. We’re closer to Scandinavia than America, Adams suggests.

Comparing ourselves to others isn’t new. Wilson-Smith says Canadians have long defined ourselves by what we’re not — not British, not French, not American.

If that’s what we’re not, what are we? People who “get along well overall, pulling in the same direction,” says Wilson-Smith. “You can be anything you want to be — as long as you’re not doing harm to anybody else.”

Wilson-Smith, a former journalist and foreign correspondent, has worked across Canada and in three dozen countries. He feels that Canadians talk about national identity more than most countries but still struggle to arrive at what exactly it means.

He points to an old comment from Pierre Trudeau, a champion of multiculturalism. Fifty years ago, as prime minister, Trudeau said this: “We should not even be able to agree upon the kind of Canadian to choose as a model, let alone persuade most people to emulate it. There is no such thing as an ideal Canadian. What could be more absurd than the concept of an all-Canadian boy or girl? What the world should be seeking, and what in Canada we must continue to cherish, are not concepts of uniformity but human values: compassion, love and understanding.”

So what does it mean to be a Canadian?

Do the values of openness, tolerance, freedom, peace, generosity, courtesy, mutual respect and fair treatment add up to a national identity? Or are those simply traits to which anyone, anywhere in the world, should aspire?

Certainly, they are. On their own, they’re not uniquely Canadian. But together, they’re a powerful combination and something to be proud of.

We probably won’t brag about that, either. It’s not our way. That’s as Canadian as possible under the circumstances.

Canada in a word

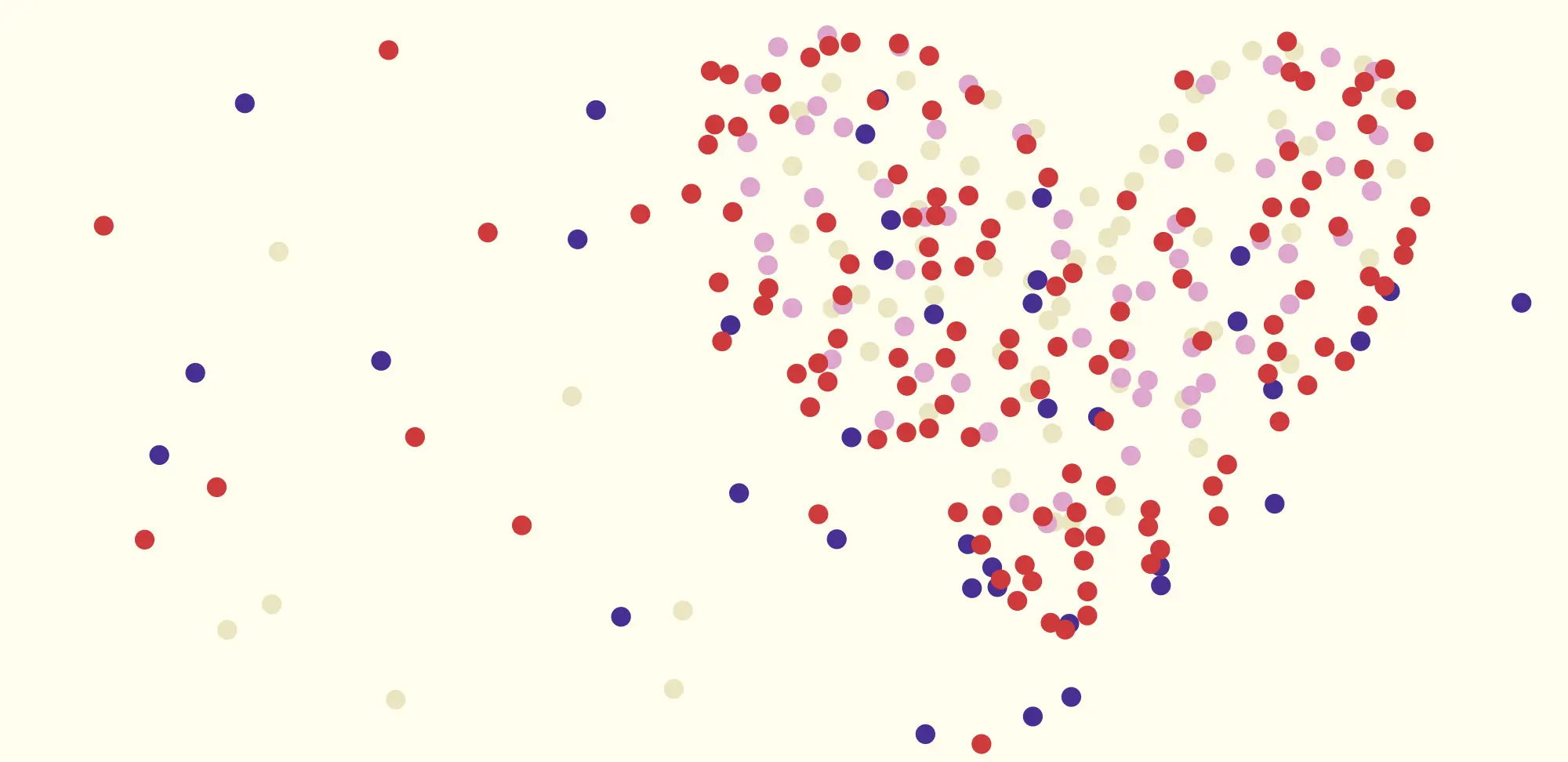

In one word, what says “Canadian” to you? We asked RTOERO members on Facebook, and 144

of you told us. You gave us 62 different answers, but there was a clear number 1: eh. That was the landslide winner, with 24 votes. Coming in second, with eight votes, was sorry, and third, with seven votes, was hockey.

This was a diverse list (and diversity got one vote). A lot of choices had to do with our reputation for openness: accepting, compassion, considerate, kindness, caring, sharing, multicultural and just plain nice.

Another group of members had food on their mind, with bacon, BeaverTails, poutine and a bunch of Timmies and maple syrup.

A few animals got a shout-out: goose, beaver and blue jay. Somewhat surprisingly, snow only received two votes; winter, just one.

To everyone who responded, thank you — that got a couple of votes too.