Imagine: Just 19 years old, and soon to have a newly minted teaching certificate in my back pocket! It was the spring of 1955. My Ottawa Teachers’ College year was coming to a close. I did not realize at the time that I was on the threshold of a 34-year career during one of the most exciting times in education. Without question, for a beginning teacher in Ontario in 1955, teaching was the opportunity of a lifetime. I had opted for a profession with endless possibilities and great potential, if I was willing to make the effort to succeed.

There were hundreds of ads for teaching positions, filling several pages of the major newspapers every single week, from every school board in Ontario. I had no idea where I wanted to teach, and so I was literally waiting for something to fall into my lap — and it did.

One memorable day, the college principal called me out of class with a surprise. Knowing that I had been a keen army cadet throughout high school, he suggested that I attend an interview with officials who were recruiting teachers for the Camp Petawawa army schools at that very moment in his office.

The details of the interview are now foggy, but I do remember one of the interviewers asking me what my hobbies were. Hobbies? I was a greenhorn kid from a dairy farm in eastern Ontario, where work was the only hobby I knew. I blurted out, “Hunting and fishing.” He sarcastically remarked, “That should go over well in the classroom.” After hearing his response, I felt my chances were pretty slim, but I got the job and would be teaching Grade 4.

I was thrilled to have my very first job, with its starting annual salary of $2,400. Although it was slightly above the going rate of other school boards in the area, this pitiful stipend was equivalent to an unskilled labourer’s wage.

But I was in on the ground floor of my career. It was a time of unprecedented expansion. During my first 15 years of teaching elementary school, enrolment in Ontario grew by almost 600,000 students before tapering off in the 1970s. Little one-room schools were closing, and thousands of new schools were being built. Teacher shortages became a serious problem, forcing school boards to compete aggressively to hire new staff.

The two schools in Camp Petawawa enjoyed an excellent reputation under the leadership of a strong-willed, dynamic supervising principal. The schools were well-equipped and well organized, with effective discipline standards. The children came from fairly advantaged homes, with stay-at-home mothers on hand when they went home at noon for their lunch break. They were a pleasure to teach. At that time, words such as autistic, hyperactive and attention deficit disorder were not part of our vocabulary when referring to students.

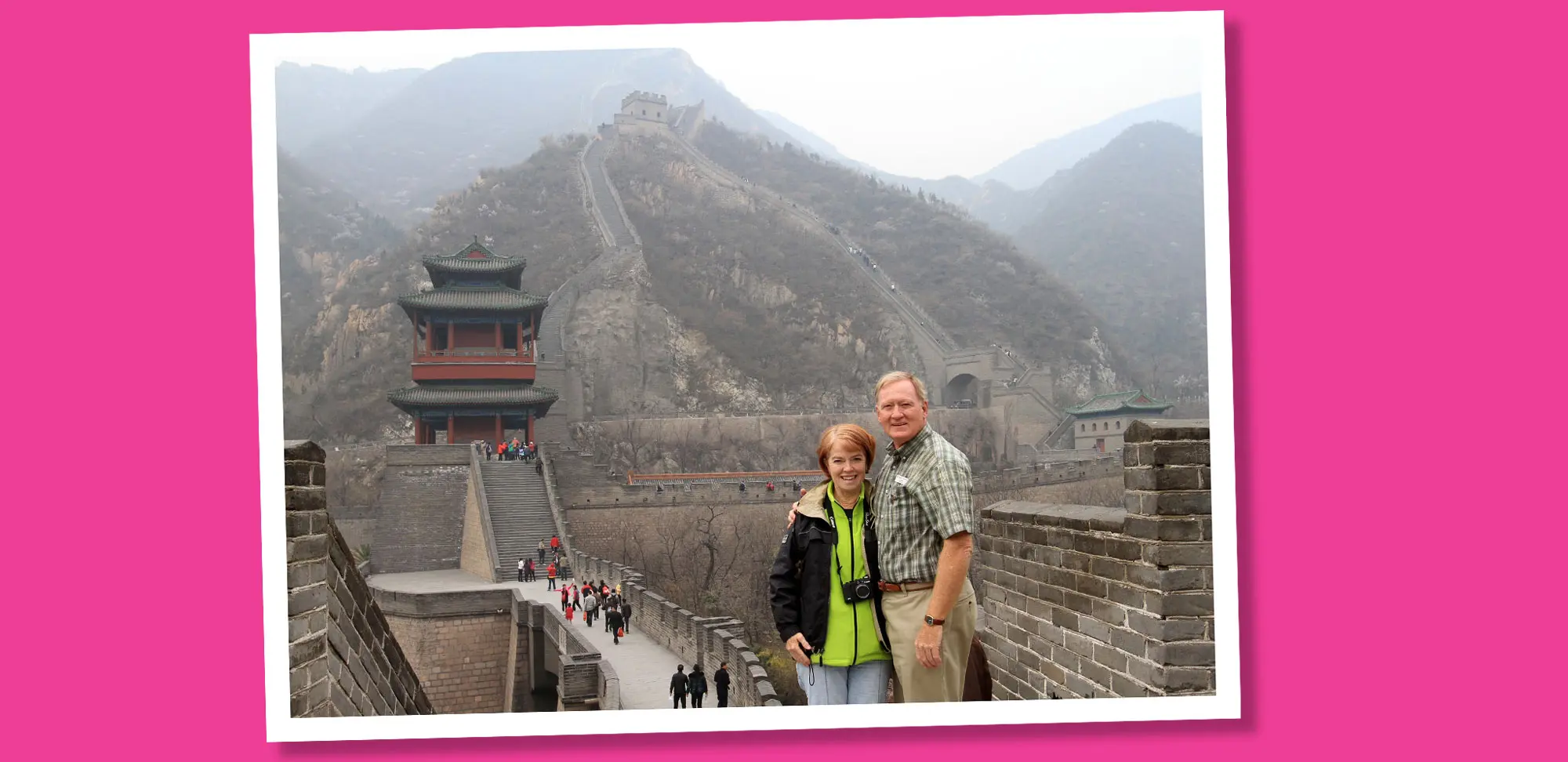

I taught Grade 4 for two years in the junior school; in my third year, I moved to Grade 6 in the senior school. In my second year, I met my future wife, Cathy, who was a new teacher on staff. We married in September 1957. After completing my very first university course by correspondence from McMaster University, I quickly decided that there had to be a better way to obtain a degree.

Queen’s University appealed to me, as it was in familiar territory. In the spring of 1958, I saw an opportunity to move to Kingston, Ont., after spotting a teaching ad from Fort Henry Heights army schools, which were located nearby. I applied and landed a vice-principal position in its junior school.

At the time, school boards encouraged teachers to improve their academic qualifications and backed this up with financial incentives. They built salary increases into teacher contracts for every five university courses completed, and a hefty increase for completion of a BA degree. After some years, and much burning of the midnight oil, my initially pitiful salary started to resemble a living wage. By the end of my career, I was earning a very respectable income — 30 times higher than my starting salary.

The focus of my personal life changed dramatically after moving to Kingston. I was a now a family man with a young daughter. We purchased a tiny house in a quiet suburb of the city, about 15 minutes from my work.

The Fort Henry school was another exceptionally rewarding work experience, with happy kids, supportive colleagues and a dedicated principal. During my time there, I taught grades 5 through 8. I finished my BA degree at Queen’s through night school and summer school, and my bachelor of education at the University of Toronto after completing required assignments and one summer’s attendance on campus.

It was not all smooth sailing. There were several lean years when money was very tight, making me wonder sometimes if I should have heeded a close friend’s repeated advice to quit teaching for a better-paying job. He was a farm machinery salesman earning several times my meagre salary.

I am fond of telling a story about a conversation I had with Cathy in my fourth year of teaching, just after we had moved to Kingston. We had a young child and a bare-bones, recently purchased little house in the suburbs. However, we were really scraping bottom financially. It was near payday at the end of the month when she said, “We have nothing for dinner. I will have to make porridge.” I became irate and said, “There is no way we are having porridge for dinner!” I scrambled around and found $1 in change. I went to the grocery store and bought three pounds of hamburger for that little pile of change. Barbecued hamburger sounded like a much better dinner than porridge.

My family and I spent seven rewarding years in Kingston, where we enjoyed our lives and made close friends, many of whom were teaching colleagues. In 1965, much to our friends’ dismay, we decided to move to Toronto so that I could obtain a master of education degree at the University of Toronto. They could not believe that we would leave our comfortable life and pull up stakes to move to a big city.

Jobs were plentiful. I obtained a teaching position with the Etobicoke Board of Education as vice-principal in a junior school. It was the right move, but with 75 elementary schools, it was a much bigger pond than the three-school Fort Henry board. I was going to have to prove myself, or gradually sink into obscurity among the hundreds of teachers employed by this board.

The gods were with me. I spent four years in two different schools as a teaching vice-principal and obtained my master of education degree plus an Ontario school inspector certificate. Then I was appointed principal of a small school in southern Etobicoke.

At last I had the opportunity to run my own show. After 14 years in the classroom, teaching every grade from 2 through 8, I felt that I was ready.

The principalship was the job that I loved best. I couldn’t wait to get to work in the morning. Every day was different. Every day was challenging. Every day was exciting. With effective and positive support from board administrators, I was able to implement the board’s policies and programs to enable its teachers to perform their jobs effectively. As principal I had one goal in mind: to strive for excellence.

Only two unfortunate provincewide fads stand out during my career. The open-plan school and the whole-language learn-to-read program were foisted on teachers by school boards throughout the province. Swept along by their popularity and the Ministry of Education’s avid recommendation that these were front-line progressive education initiatives, the Etobicoke board invested heavily in both. Uncharacteristically, Etobicoke did not do its homework. The first fad was short-lived, but the second was long-lasting and much more detrimental to students.

In spite of these missteps, a multitude of progressive initiatives were implemented during my time in education. School boards were flush with money. Teachers’ salaries increased dramatically, beginning in about 1965, along with their rapidly improving qualifications. And school boards expected teachers to keep up with the latest developments in education research by upgrading their skills and knowledge.

Part-time university courses were easily accessible. Free, board-sponsored, in-service evening training sessions were held for teachers wanting to learn new skills in every subject area. The number of professional development days increased, allowing teachers to attend education seminars focused on new Ministry of Education initiatives and kids to enjoy some time off. Teachers had opportunities to attend out-of-town education conferences or apply for a sabbatical year to earn a postgraduate degree. An innovative four-over-five salary plan allowed teachers to take a 20 per cent reduction in salary for four years and then take a break and enjoy the fifth year off — with pay — to do whatever they wished.

School boards actively supported teachers. They chose highly effective classroom teachers for consultant positions geared specifically to assist fellow instructors who needed help. Large urban boards established their own curriculum departments staffed by consultants to develop in-house teaching guides.

The Ministry of Education conducted certificate programs for teachers who wished to obtain qualifications in specialized areas, such as special education, early childhood education, the use of audio-visual equipment in the classroom and English as a second language instruction. The opportunities for teachers to improve their expertise at little cost were endless, and these enhanced skills proved to be of enormous benefit to many children.

Far-sighted, innovative leadership at the ministry and school board levels led to new programs that were advantageous for young children. Senior kindergarten for five-year-olds, while not compulsory, gradually became commonplace throughout Ontario, followed later by junior kindergarten for four-year-olds. These highly popular programs added thousands of students and teachers to the system. Play-based learning helped give children from different backgrounds the foundational skills they needed for more formal learning in Grade 1.

Before the 1970s, many children with special needs were excluded from school or offered programs that were little more than child care. This changed with the introduction of smaller, special education classes for children with learning disabilities in the ’70s. They were taught by highly skilled teachers with the help of teaching assistants who were trained to help students develop effective learning strategies.

In this era, English as a second language (ESL) classes and summer school programs were introduced to benefit new Canadian children who were flooding into Ontario. A Frenchimmersion program also debuted on a limited basis to encourage bilingualism. It soon became very popular and expanded significantly.

Ontario’s 1968 evaluation of the education system, known as the Hall-Dennis Report, changed the way students were treated within schools. Among its many recommendations, it advocated the introduction of special education classes. It soundly condemned the practice of failing students and corporal punishment. Strapping — the controversial, barbaric practice of slapping children on the palms of their hands with a leather strap — had been an ingrained part of the system ever since Ontario’s public education began, but the report recommended it be banned. The strap gradually fell into disuse in Ontario in the early 1970s but was not formally abolished in Canadian schools until the 1990s.

This same report recommended replacing student failures with “continuous learning,” or, more simply stated, allowing children to progress at their own rate. This controversial idea gradually caught on, and outright failure became frowned upon in favour of children moving to the next level along with their own age group. It was a progressive move — educators knew well that requiring struggling students to repeat their year had little academic merit and very negative, emotional consequences for children.

When I started my first teaching job in 1955, I had no idea that I was on the precipice of so many exciting changes or personal opportunities. During my 34-year career, education was transformed, from banning the strap to replacing failure with continuous learning. Schools became more inclusive for all sorts of students, who were vastly more diverse than my cohort, which came from fairly advantaged homes with stay-at-home mothers.

My own program of continuous learning eventually resulted in my earning a doctorate, with a focus on how teachers allocate their time. And I had no inkling that my meagre starting salary would grow so much, or that teaching would prove to be so personally satisfying.